Arts & Culture

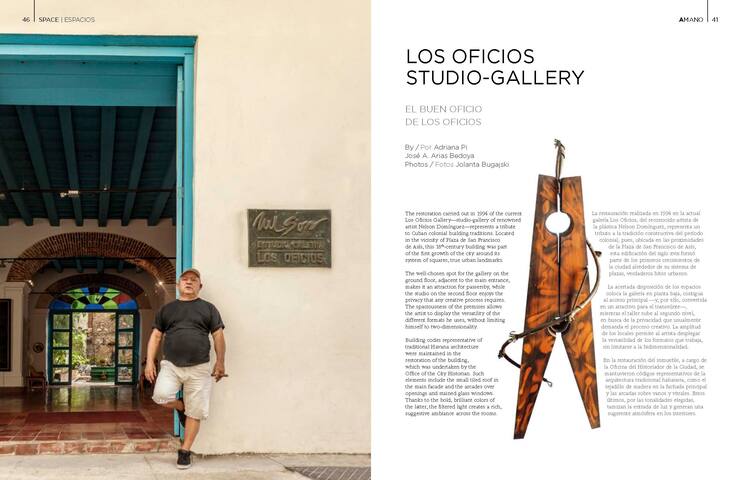

The restoration carried out in 1994 of the current Los Oficios Gallery—studio-gallery of renowned artist Nelson Domínguez—represents a tribute to Cuban colonial building traditions. Located in the vicinity of Plaza de San Francisco de Asís, this 18th-century building was part of the first growth of the city around its system of squares, true urban landmarks.

The well-chosen spot for the gallery on the ground floor, adjacent to the main entrance, makes it an attraction for passersby, while the studio on the second floor enjoys the privacy that any creative process requires. The spaciousness of the premises allows the artist to display the versatility of the different formats he uses, without limiting himself to two-dimensionality.

Building codes representative of traditional Havana architecture were maintained in the restoration of the building, which was undertaken by the Office of the City Historian. Such elements include the small tiled roof in the main facade and the arcades over openings and stained glass windows. Thanks to the bold, brilliant colors of the latter, the filtered light creates a rich, suggestive ambiance across the rooms.

The brick arches have been exposed intentionally, which, supported by the lighting design, are emphasized as aesthetic elements beyond their structural function.

One of the most attractive components is the common rafter frame roof, which gives the rooms a feeling of amplitude and is distinct from the ground floor, whose ceiling is a mezzanine made of beams and planks. Both are significantly well preserved. The color palette contributes to the coherence of the project and matches the color range of the colonial era, especially the so-called “Havana blue” of the woodwork, an allusion to historical referents.

The marble veneer flooring on the second level is also an interesting element. Although marble has been traditionally used for this purpose, here it has been reinterpreted and given a more contemporary approach, thanks to the shape and arrangement of the slabs.

This intervention is a positive example of the rescue of colonial architecture, by harmoniously combining traditional typologies with current treatments. The successful refunctionalization of a building that is representative of domestic architecture—it was the residence of Presbyter Pedro Benedicto Hourrutinier—into a studio-gallery is due, to a large extent, to the proper use of each space and a respectful attitude towards heritage values. This is why this space for creation and exhibition at Oficios Street No. 166, between Amargura and Teniente Rey streets, Old Havana, is as worthy to be admired as the art of Nelson Domínguez.

https://amanoempire.com/los-oficios-studio-gallery/

Art Gallery Los Oficios

166 OficiosThe restoration carried out in 1994 of the current Los Oficios Gallery—studio-gallery of renowned artist Nelson Domínguez—represents a tribute to Cuban colonial building traditions. Located in the vicinity of Plaza de San Francisco de Asís, this 18th-century building was part of the first growth of the city around its system of squares, true urban landmarks.

The well-chosen spot for the gallery on the ground floor, adjacent to the main entrance, makes it an attraction for passersby, while the studio on the second floor enjoys the privacy that any creative process requires. The spaciousness of the premises allows the artist to display the versatility of the different formats he uses, without limiting himself to two-dimensionality.

Building codes representative of traditional Havana architecture were maintained in the restoration of the building, which was undertaken by the Office of the City Historian. Such elements include the small tiled roof in the main facade and the arcades over openings and stained glass windows. Thanks to the bold, brilliant colors of the latter, the filtered light creates a rich, suggestive ambiance across the rooms.

The brick arches have been exposed intentionally, which, supported by the lighting design, are emphasized as aesthetic elements beyond their structural function.

One of the most attractive components is the common rafter frame roof, which gives the rooms a feeling of amplitude and is distinct from the ground floor, whose ceiling is a mezzanine made of beams and planks. Both are significantly well preserved. The color palette contributes to the coherence of the project and matches the color range of the colonial era, especially the so-called “Havana blue” of the woodwork, an allusion to historical referents.

The marble veneer flooring on the second level is also an interesting element. Although marble has been traditionally used for this purpose, here it has been reinterpreted and given a more contemporary approach, thanks to the shape and arrangement of the slabs.

This intervention is a positive example of the rescue of colonial architecture, by harmoniously combining traditional typologies with current treatments. The successful refunctionalization of a building that is representative of domestic architecture—it was the residence of Presbyter Pedro Benedicto Hourrutinier—into a studio-gallery is due, to a large extent, to the proper use of each space and a respectful attitude towards heritage values. This is why this space for creation and exhibition at Oficios Street No. 166, between Amargura and Teniente Rey streets, Old Havana, is as worthy to be admired as the art of Nelson Domínguez.

https://amanoempire.com/los-oficios-studio-gallery/

The story of ZULU Bolsos was born at the time of the so-called Special Period in the early 1990’s when the collapse of the USSR and the socialist bloc meant for Cuba the loss of its most important economic ally. It was a decade of enormous material difficulties, marked by the lack of the most basic elements and by the dizzying development of the creativity and resourcefulness of the Cuban people. During those years, the creators of ZULU, Hilda Zulueta and her two daughters, Odamis and Mady, were forced to begin to resolver (roughly, to solve, to get by), a term that began to be used then, and to this day defines a way to survive certain economic difficulties. Hilda was a high-school Math teacher, Odamis had just graduated in Mechanical Engineering and Mady was studying Art History at a time when prices skyrocketed and the family wage was not enough. So they began to collect leftover pieces of leather from a nearby shoe factory where Odamis was performing social service as a recent university graduate. Once at home, they would place them on the floor and make puzzles with them until they managed to design a handbag that they then sold through their artisan friends at the former G Street Fair, in El Vedado neighborhood. With hardly any tools, materials or experience in design, their household economy got a certain boost from the sale of their handmade bags. But it turned out that they were very good at it and, as it often happens, what had started as a necessity became a passion.

As a result of what they call “empirical work,” their creative process, which over the years has been based on the trial and error method, is totally personal, as Hilda explains: “There’s a strong craft tradition in Cuba, but we were pioneers in this kind of design. By starting to work freely, without being connected to a tradition or an institution, we were breaking new grounds without realizing it.” Thanks to the tenacity and creativity of these three women, since 2011, ZULU has its own store in Old Havana and a small team built from scratch. Their designs, which are based on observing day-to-day Cuban life, have become pacesetters. Hilda comments on where they draw inspiration from: “We have always been very observant. In order to solve math problems, you need to be very observant. This I learned and then passed it on to my daughters. Our aim is to make our bags, first and foremost, Cuban and at the same time modern. We don’t copy anything—what’s most important is that we want them to be unique and to reflect our reality.”

Using hand-treated leather, ZULU makes elegant, urban and, above all, original handbags thanks to the effective balance between a European-inspired sobriety and an exuberance that validates its Caribbean roots. This is now becoming a trend among younger designers, but in the 90s, it was a rarity. Hilda, Odamis and Mady accompany their team during the entire creative process, while stamping their own personal touch, which they have named “zuleado,” a technique they created themselves consisting of exposing the irregular edges that remain after tanning the leather. This is symbolic of their beginnings—where apparently there’s nothing, there may be an opportunity—and of the respect they have towards the material they work with: “You fall in love with this pursuit because it is very noble. Leather adapts itself to whatever shape you want to give it, and this fills your spirit.”

In 2016, ZULU took part in FIART (International Craft Fair) and won the Best Product Award. That same year they were also winners of the Ellas Crean Prize of the Spanish Embassy, with a training proposal for young women from Havana who wished to learn the trade of working leather. Their long-term purpose is to make a social impact on the community and to transmit the love for this profession: “Looking forward, we would like to be able to grow and teach... To pass on what we have been learning all by ourselves all these years to people who are interested in this line of work, so that they can have more autonomy.”

Regarding the situation of design in Cuba, they are very clear about it: creativity is everywhere, the problem lies in having access to materials that allow improvement: “I believe that young people are doing things with plenty of enthusiasm, what is missing is a wholesale business where craftspeople can go and get what they need to make their work better.” Even so, they already know that difficulties do not prevent from fulfilling one’s dreams. The obstacles found along the way have taken them along unsuspected paths and their success is proof of that.

https://amanoempire.com/zulu-for-the-love-of-leather-diseno-a-flor-de-piel/

ZULU Bolsos

MurallaThe story of ZULU Bolsos was born at the time of the so-called Special Period in the early 1990’s when the collapse of the USSR and the socialist bloc meant for Cuba the loss of its most important economic ally. It was a decade of enormous material difficulties, marked by the lack of the most basic elements and by the dizzying development of the creativity and resourcefulness of the Cuban people. During those years, the creators of ZULU, Hilda Zulueta and her two daughters, Odamis and Mady, were forced to begin to resolver (roughly, to solve, to get by), a term that began to be used then, and to this day defines a way to survive certain economic difficulties. Hilda was a high-school Math teacher, Odamis had just graduated in Mechanical Engineering and Mady was studying Art History at a time when prices skyrocketed and the family wage was not enough. So they began to collect leftover pieces of leather from a nearby shoe factory where Odamis was performing social service as a recent university graduate. Once at home, they would place them on the floor and make puzzles with them until they managed to design a handbag that they then sold through their artisan friends at the former G Street Fair, in El Vedado neighborhood. With hardly any tools, materials or experience in design, their household economy got a certain boost from the sale of their handmade bags. But it turned out that they were very good at it and, as it often happens, what had started as a necessity became a passion.

As a result of what they call “empirical work,” their creative process, which over the years has been based on the trial and error method, is totally personal, as Hilda explains: “There’s a strong craft tradition in Cuba, but we were pioneers in this kind of design. By starting to work freely, without being connected to a tradition or an institution, we were breaking new grounds without realizing it.” Thanks to the tenacity and creativity of these three women, since 2011, ZULU has its own store in Old Havana and a small team built from scratch. Their designs, which are based on observing day-to-day Cuban life, have become pacesetters. Hilda comments on where they draw inspiration from: “We have always been very observant. In order to solve math problems, you need to be very observant. This I learned and then passed it on to my daughters. Our aim is to make our bags, first and foremost, Cuban and at the same time modern. We don’t copy anything—what’s most important is that we want them to be unique and to reflect our reality.”

Using hand-treated leather, ZULU makes elegant, urban and, above all, original handbags thanks to the effective balance between a European-inspired sobriety and an exuberance that validates its Caribbean roots. This is now becoming a trend among younger designers, but in the 90s, it was a rarity. Hilda, Odamis and Mady accompany their team during the entire creative process, while stamping their own personal touch, which they have named “zuleado,” a technique they created themselves consisting of exposing the irregular edges that remain after tanning the leather. This is symbolic of their beginnings—where apparently there’s nothing, there may be an opportunity—and of the respect they have towards the material they work with: “You fall in love with this pursuit because it is very noble. Leather adapts itself to whatever shape you want to give it, and this fills your spirit.”

In 2016, ZULU took part in FIART (International Craft Fair) and won the Best Product Award. That same year they were also winners of the Ellas Crean Prize of the Spanish Embassy, with a training proposal for young women from Havana who wished to learn the trade of working leather. Their long-term purpose is to make a social impact on the community and to transmit the love for this profession: “Looking forward, we would like to be able to grow and teach... To pass on what we have been learning all by ourselves all these years to people who are interested in this line of work, so that they can have more autonomy.”

Regarding the situation of design in Cuba, they are very clear about it: creativity is everywhere, the problem lies in having access to materials that allow improvement: “I believe that young people are doing things with plenty of enthusiasm, what is missing is a wholesale business where craftspeople can go and get what they need to make their work better.” Even so, they already know that difficulties do not prevent from fulfilling one’s dreams. The obstacles found along the way have taken them along unsuspected paths and their success is proof of that.

https://amanoempire.com/zulu-for-the-love-of-leather-diseno-a-flor-de-piel/

Architecture

We have wanted to reflect the actions that are being carried out towards the celebration of the 500th anniversary of the founding of Havana in November 2019. Must be seen the most significant symbols of the Cuban capital Havana and it's amazing architecture

At the beginning of the second half of the 19th century, a residential development, distant from previous Havana expansions, was taking shape while ensuring its undeniable uniqueness. The district known as El Vedado was born near the mouth of the Almendares River with the added benefit of being associated with the coastal landscape. hA regular street grid, rotated to make the best use of the breezes; tree-lined streets, parks and promenades; the design of its streets, sidewalks and parterres, which years later would facilitate the arrival of the automobile; city blocks reserved for services and public spaces were just some of the many novel features of the urban project.

Throughout its 150 years of existence, El Vedado has accumulated the wide and varied architectural repertoire that has characterized it, endowing it with an incredible wealth. In the early 20th century, it was recognized as the most elegant neighborhood in the city, and it has remained, over time, a preferred space for Habaneros, both for its attractive and pleasant surroundings and for the centrality acquired over the years.

The porches and front yards, which were required by the urban project, favored the consistency of the resulting image, which also received the contribution of the excellent architecture inserted in its blocks, irrespective of typological variety, formal expression and the hierarchy of the buildings. Although El Vedado is associated with the neighborhood of the elite and the aristocracy of the first decades of the Republic—view based on the magnificence of the residences built during the second and third decades of the 20th century—before that time and especially after that period, buildings were designed for different social groups.

Other manifestations of residential architecture, mainly those created for the growing middle class, which were not so grandiose, yet bearers of undoubted elegance and high-quality construction, would occupy a large part of urban spaces. Different types of apartment buildings, from the most luxurious to the most unpretentious, were added to the architectural landscape.The advantages of the innovative urbanism made it possible for spectacular palaces of the Republican era, sober neoclassical hacienda style houses, attractive eclectic villas, modest semi-detached and terraced houses, and even poor dwellings in hidden tenements, inside the block, flanked by eclectic porches, to coexist in total harmony, achieved thanks to the imperatives of urban planning and the undeniable quality of the construction itself.

https://amanoempire.com/el-vedado-excellence-of-residential-architecture/

140 (рекомендации местных жителей)

Vedado

At the beginning of the second half of the 19th century, a residential development, distant from previous Havana expansions, was taking shape while ensuring its undeniable uniqueness. The district known as El Vedado was born near the mouth of the Almendares River with the added benefit of being associated with the coastal landscape. hA regular street grid, rotated to make the best use of the breezes; tree-lined streets, parks and promenades; the design of its streets, sidewalks and parterres, which years later would facilitate the arrival of the automobile; city blocks reserved for services and public spaces were just some of the many novel features of the urban project.

Throughout its 150 years of existence, El Vedado has accumulated the wide and varied architectural repertoire that has characterized it, endowing it with an incredible wealth. In the early 20th century, it was recognized as the most elegant neighborhood in the city, and it has remained, over time, a preferred space for Habaneros, both for its attractive and pleasant surroundings and for the centrality acquired over the years.

The porches and front yards, which were required by the urban project, favored the consistency of the resulting image, which also received the contribution of the excellent architecture inserted in its blocks, irrespective of typological variety, formal expression and the hierarchy of the buildings. Although El Vedado is associated with the neighborhood of the elite and the aristocracy of the first decades of the Republic—view based on the magnificence of the residences built during the second and third decades of the 20th century—before that time and especially after that period, buildings were designed for different social groups.

Other manifestations of residential architecture, mainly those created for the growing middle class, which were not so grandiose, yet bearers of undoubted elegance and high-quality construction, would occupy a large part of urban spaces. Different types of apartment buildings, from the most luxurious to the most unpretentious, were added to the architectural landscape.The advantages of the innovative urbanism made it possible for spectacular palaces of the Republican era, sober neoclassical hacienda style houses, attractive eclectic villas, modest semi-detached and terraced houses, and even poor dwellings in hidden tenements, inside the block, flanked by eclectic porches, to coexist in total harmony, achieved thanks to the imperatives of urban planning and the undeniable quality of the construction itself.

https://amanoempire.com/el-vedado-excellence-of-residential-architecture/

The former Colegio de San Pablo, founded by the Cuban poet and patriot Rafael María de Mendive, became in September 2018 an elementary school that bears his name.

Restored by the Office of the Historian of the City of Havana (OHCH), the building is located on 88 Prado Avenue (today 266 Prado Avenue) between Ánimas and Trocadero streets. Here, Mendive served as principal of the Higher Secondary School for Boys, a public educational institution, and opened the private school Colegio de San Pablo between 1867 and 1869. José Martí enrolled in the School for Boys around mid-term in 1865, and then, when the San Pablo School opened, the Cuban National Hero, who had already established a close relationship with his teacher, appeared on the school roll.

Architect Norma Pérez-Trujillo Tenorio, head of the Department of Rehabilitation and Heritage Preservation of the OHCH Investment Department provided some details about the building’s restoration: “Given the historical relevance of the property and at the request of Dr. Eusebio Leal, Historian of the City of Havana, a technical assessment was carried out. A team of archaeologists was commissioned to appraise the merits that remained in the building after the enormous transformations that had been performed before. The most extensive ones most likely date back to the 1950s after its purchase by the General Electric Company,” she explained.

https://amanoempire.com/rebirth-of-school-where-jose-marti-studied/

Jose Marti

The former Colegio de San Pablo, founded by the Cuban poet and patriot Rafael María de Mendive, became in September 2018 an elementary school that bears his name.

Restored by the Office of the Historian of the City of Havana (OHCH), the building is located on 88 Prado Avenue (today 266 Prado Avenue) between Ánimas and Trocadero streets. Here, Mendive served as principal of the Higher Secondary School for Boys, a public educational institution, and opened the private school Colegio de San Pablo between 1867 and 1869. José Martí enrolled in the School for Boys around mid-term in 1865, and then, when the San Pablo School opened, the Cuban National Hero, who had already established a close relationship with his teacher, appeared on the school roll.

Architect Norma Pérez-Trujillo Tenorio, head of the Department of Rehabilitation and Heritage Preservation of the OHCH Investment Department provided some details about the building’s restoration: “Given the historical relevance of the property and at the request of Dr. Eusebio Leal, Historian of the City of Havana, a technical assessment was carried out. A team of archaeologists was commissioned to appraise the merits that remained in the building after the enormous transformations that had been performed before. The most extensive ones most likely date back to the 1950s after its purchase by the General Electric Company,” she explained.

https://amanoempire.com/rebirth-of-school-where-jose-marti-studied/

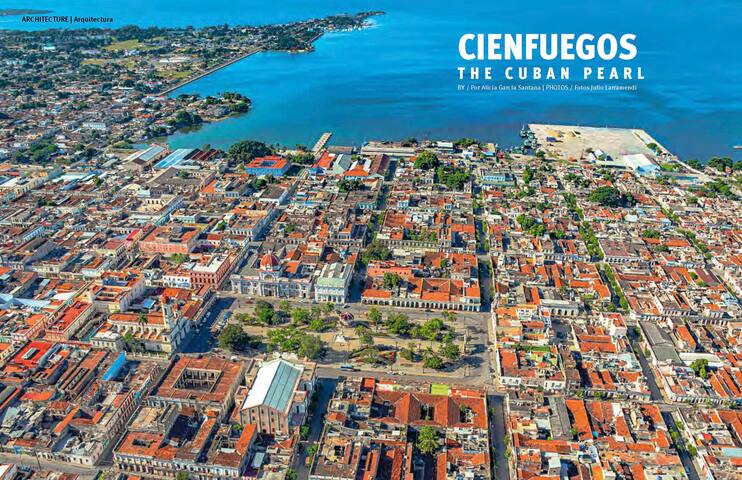

Cienfuegos was one of the cities that arose from the powerful levers that transformed life in Cuba in the early decades of the 19th century 1. Its urban and architectural trajectory resembles that of cities founded in the same period, some in the central region, like Sagua La Grande (1812), Cárdenas (1828) and Caibarién (1831), a group to which we can add the town of Colón (1836), in the central part of today’s Matanzas Province, but communicated with ports thanks to the early establishment of the railroad in the territory. And although the city of Matanzas was founded in 1693, it reached its urban and architectural consolidation in the early decades of the 19th century. They are all very different from the illustrious towns established in the 16th century, represented by nearby Trinidad (1514), Sancti Spíritus (1515) and Remedios (ca. 1520-1528).

The early settlements were basically rural until the end of the 18th century, a long historical period that witnessed the development of the local-creole version that shaped the urban and architectural entity upon which these populations would evolve. The life in the city by individuals belonging to families who had settled there from the early days and who were members of powerful local oligarchies led to a conservatism that motivated the permanence of certain ways of life, including those related to the layout of the city, its buildings and dwellings. The commercial dynamics of the ports in the 19th century radically changed the pace of life and broke the isolation of populations from each another and from the outside world.

Ports opened the nation to the world, and merchants, both Spaniards and foreigners, attained a central role in citizen life, while the most prosperous became landowners. An upper social class was consolidated. Their superiority did not rely on lineage but on money—the latter made it possible to fill the gap in genealogy. The generalization of the printing press and the circulation of newspapers allowed access to information of all kinds. Numerous foreigners, many of whom were involved in construction and crafts, settled down in the city. This led to expanding the scope of architectural and urban undertakings. Growth in the standard of living changed social customs, which went beyond the narrow framework of religious devotions to incorporate different activities of a civil nature.

The modern economic and social ideas engendered in the last third of the 18th century under the Enlightenment influenced the actions of the leading groups, who tended to the physical and functional modernization of cities. The notions of progress consolidated the efficiency of the regular urban typology. For Spanish-American purposes, the orthogonal city with a central square, encircled by porticos and surrounded by buildings representative of religious and public power, was well known since the 16th century given the existence of countless towns designed on a grid, a model used by the Spanish since the dawn of that century. The recovery of the grid plan in the 18th century was accompanied by propositions that emphasized the civil and ornamental significance of public spaces with resources derived from Baroque and enlightened urbanism, such as street furniture for functional or decorative purposes, porches on promenades and main streets in imitation of the Hellenistic plan and landscaped green areas, along with administrative measures.

A different city arose under the Enlightenment, one which was formally defined by its unity, axiality, symmetry, regularity, proportion and rationality. It displayed an unprecedented landscape due to the fusion, all along the streets, of structures that were uniform in size, proportional to the width of the streets, and enhanced by elements of neoclassic inspiration, which, in their recurrence, configured an unbroken rhythm. Stylistically, neoclassicism is precisely the current that prevails in the 19th century, and one of the main foundations of the urban and architectural unity of our towns.

The most significant aspect of 19th-century dwellings in Cienfuegos derived from the new typological proposals of the second half of the century. As we have pointed out, the geographical location of Cienfuegos in the central part of the Island determined the intervention of diverse influences—some from the nearby early towns, especially from Trinidad; others, from the Matanzas-Cárdenas-Sagua region—which, when contaminated and mixed, resulted in the definition of a type that was recognizable since the mid-19th century, an expression of a general trend affecting dwellings. But this did not end here. Subsequently or at the same time, a new type of dwelling was being built. This type of house assimilated elements derived from the so called casa-quinta, while adopting solutions—coming from the United States—that were alien to the Spanish tradition of houses with a courtyard, until then dominant as the model of Cuban vernacular dwellings. This new house featured side gardens with access from the street, inserted into the urban grid. Combined with the previous type of house, this new type gave rise to the expression par excellence of Cienfuegos 19th-century domestic architecture.

The 20th century would bring examples of wood architecture that flourished in the outskirts of the city. This had been part of its building heritage since the very beginnings of the city, but the new century would bring along refinement and uniqueness. Meanwhile, in the heart of the city and the suburbs, we find one of the most extraordinary group of eclectic residences in Cuba. These houses were signified by a marked formal coherence derived from the adoption of a “Renaissance” international type, with or without loggias on the piano nobiles, but with the main areas arranged according to the model of the previous stage, clearly a testimony to continuity and rupture. This is a signature architecture, the work of Cienfuegos natives or of professionals from other places who chose to settle permanently in the city.

The scene is completed with examples influenced by architectural styles that include Art Deco, neocolonial, rationalism, the avant-garde of the 1950s and the work developed in the new suburbs and urban developments during the second half of the 20th century. The result is the material consolidation of one of the most beautiful cities in Cuba, built on a perfectly regular grid against the silhouette of the Guamuhaya mountain range, embraced by its unfathomable and immense bay, its prodigal lands fertilized by rivers, and inhabited by individuals who proudly work and live in the Pearl of the South, or Pearl of Cuba, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2005.

https://amanoempire.com/cienfuegos-the-cuban-pearl/

57 (рекомендации местных жителей)

Cienfuegos

Cienfuegos was one of the cities that arose from the powerful levers that transformed life in Cuba in the early decades of the 19th century 1. Its urban and architectural trajectory resembles that of cities founded in the same period, some in the central region, like Sagua La Grande (1812), Cárdenas (1828) and Caibarién (1831), a group to which we can add the town of Colón (1836), in the central part of today’s Matanzas Province, but communicated with ports thanks to the early establishment of the railroad in the territory. And although the city of Matanzas was founded in 1693, it reached its urban and architectural consolidation in the early decades of the 19th century. They are all very different from the illustrious towns established in the 16th century, represented by nearby Trinidad (1514), Sancti Spíritus (1515) and Remedios (ca. 1520-1528).

The early settlements were basically rural until the end of the 18th century, a long historical period that witnessed the development of the local-creole version that shaped the urban and architectural entity upon which these populations would evolve. The life in the city by individuals belonging to families who had settled there from the early days and who were members of powerful local oligarchies led to a conservatism that motivated the permanence of certain ways of life, including those related to the layout of the city, its buildings and dwellings. The commercial dynamics of the ports in the 19th century radically changed the pace of life and broke the isolation of populations from each another and from the outside world.

Ports opened the nation to the world, and merchants, both Spaniards and foreigners, attained a central role in citizen life, while the most prosperous became landowners. An upper social class was consolidated. Their superiority did not rely on lineage but on money—the latter made it possible to fill the gap in genealogy. The generalization of the printing press and the circulation of newspapers allowed access to information of all kinds. Numerous foreigners, many of whom were involved in construction and crafts, settled down in the city. This led to expanding the scope of architectural and urban undertakings. Growth in the standard of living changed social customs, which went beyond the narrow framework of religious devotions to incorporate different activities of a civil nature.

The modern economic and social ideas engendered in the last third of the 18th century under the Enlightenment influenced the actions of the leading groups, who tended to the physical and functional modernization of cities. The notions of progress consolidated the efficiency of the regular urban typology. For Spanish-American purposes, the orthogonal city with a central square, encircled by porticos and surrounded by buildings representative of religious and public power, was well known since the 16th century given the existence of countless towns designed on a grid, a model used by the Spanish since the dawn of that century. The recovery of the grid plan in the 18th century was accompanied by propositions that emphasized the civil and ornamental significance of public spaces with resources derived from Baroque and enlightened urbanism, such as street furniture for functional or decorative purposes, porches on promenades and main streets in imitation of the Hellenistic plan and landscaped green areas, along with administrative measures.

A different city arose under the Enlightenment, one which was formally defined by its unity, axiality, symmetry, regularity, proportion and rationality. It displayed an unprecedented landscape due to the fusion, all along the streets, of structures that were uniform in size, proportional to the width of the streets, and enhanced by elements of neoclassic inspiration, which, in their recurrence, configured an unbroken rhythm. Stylistically, neoclassicism is precisely the current that prevails in the 19th century, and one of the main foundations of the urban and architectural unity of our towns.

The most significant aspect of 19th-century dwellings in Cienfuegos derived from the new typological proposals of the second half of the century. As we have pointed out, the geographical location of Cienfuegos in the central part of the Island determined the intervention of diverse influences—some from the nearby early towns, especially from Trinidad; others, from the Matanzas-Cárdenas-Sagua region—which, when contaminated and mixed, resulted in the definition of a type that was recognizable since the mid-19th century, an expression of a general trend affecting dwellings. But this did not end here. Subsequently or at the same time, a new type of dwelling was being built. This type of house assimilated elements derived from the so called casa-quinta, while adopting solutions—coming from the United States—that were alien to the Spanish tradition of houses with a courtyard, until then dominant as the model of Cuban vernacular dwellings. This new house featured side gardens with access from the street, inserted into the urban grid. Combined with the previous type of house, this new type gave rise to the expression par excellence of Cienfuegos 19th-century domestic architecture.

The 20th century would bring examples of wood architecture that flourished in the outskirts of the city. This had been part of its building heritage since the very beginnings of the city, but the new century would bring along refinement and uniqueness. Meanwhile, in the heart of the city and the suburbs, we find one of the most extraordinary group of eclectic residences in Cuba. These houses were signified by a marked formal coherence derived from the adoption of a “Renaissance” international type, with or without loggias on the piano nobiles, but with the main areas arranged according to the model of the previous stage, clearly a testimony to continuity and rupture. This is a signature architecture, the work of Cienfuegos natives or of professionals from other places who chose to settle permanently in the city.

The scene is completed with examples influenced by architectural styles that include Art Deco, neocolonial, rationalism, the avant-garde of the 1950s and the work developed in the new suburbs and urban developments during the second half of the 20th century. The result is the material consolidation of one of the most beautiful cities in Cuba, built on a perfectly regular grid against the silhouette of the Guamuhaya mountain range, embraced by its unfathomable and immense bay, its prodigal lands fertilized by rivers, and inhabited by individuals who proudly work and live in the Pearl of the South, or Pearl of Cuba, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2005.

https://amanoempire.com/cienfuegos-the-cuban-pearl/

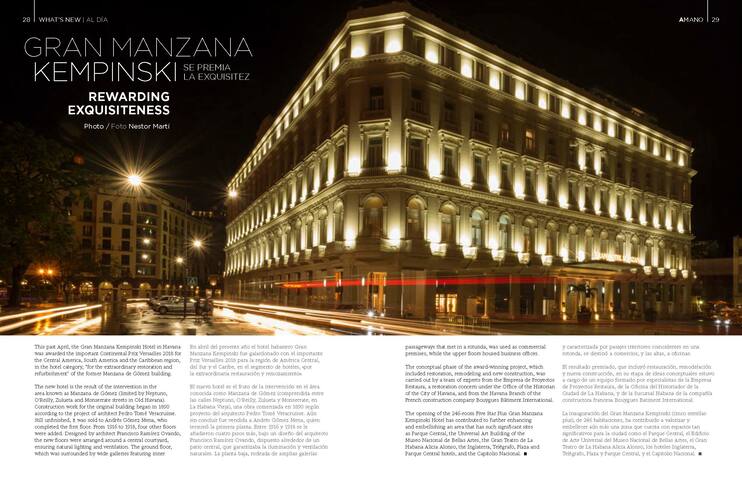

The Gran Manzana Kempinski Hotel in Havana was awarded the important Continental Prix Versailles 2018 for the Central America, South America and the Caribbean region, in the hotel category, “for the extraordinary restoration and refurbishment” of the former Manzana de Gómez building.

The new hotel is the result of the intervention in the area known as Manzana de Gómez (limited by Neptuno, O’Reilly, Zulueta and Monserrate streets in Old Havana). Construction work for the original building began in 1890 according to the project of architect Pedro Tomé Veracruisse. Still unfinished, it was sold to Andrés Gómez Mena, who completed the first floor. From 1916 to 1918, four other floors were added. Designed by architect Francisco Ramírez Ovando, the new floors were arranged around a central courtyard, ensuring natural lighting and ventilation.

https://amanoempire.com/gran-manzana-kempinski-rewarding-exquisiteness-gran-manzana-kempinski-se-premia-la-exquisitez/

100 (рекомендации местных жителей)

Gran Hotel Manzana Kempinski La Habana

AgramonteThe Gran Manzana Kempinski Hotel in Havana was awarded the important Continental Prix Versailles 2018 for the Central America, South America and the Caribbean region, in the hotel category, “for the extraordinary restoration and refurbishment” of the former Manzana de Gómez building.

The new hotel is the result of the intervention in the area known as Manzana de Gómez (limited by Neptuno, O’Reilly, Zulueta and Monserrate streets in Old Havana). Construction work for the original building began in 1890 according to the project of architect Pedro Tomé Veracruisse. Still unfinished, it was sold to Andrés Gómez Mena, who completed the first floor. From 1916 to 1918, four other floors were added. Designed by architect Francisco Ramírez Ovando, the new floors were arranged around a central courtyard, ensuring natural lighting and ventilation.

https://amanoempire.com/gran-manzana-kempinski-rewarding-exquisiteness-gran-manzana-kempinski-se-premia-la-exquisitez/

Ironwork in Cuban colonial architecture acquired a gradual

leading role resulting from the use of simple elements such as

door fittings, wrought iron door knockers and handles, wrought iron nails on doors and the addition of a novel, late 18th century device, the lamp bracket, which began to be used for street lighting. Pre-manufactured or ready-to-assemble products brought by way of companies based in Spain, England, the United States, France, Germany and Belgium coexisted with pieces forged in Cuban workshops.

The golden age and heyday of blacksmithing is evident in

19th-century architecture, which is classified as essentially

neoclassical. Wrought-iron railings, iron bars for balcony

structures and wrought iron gates on stairs were built in

Havana’s foundries under the influence of the use of ironwork

in architecture in such Spanish cities as Madrid, Seville and

Cadiz. This new trend brought a penchant for modernizing the appearance of historical buildings, but it did not come without criticism. The 20th-century scholar Francisco Prat Puig described the supporters of the trend as arrogant and irreverent for destroying or adulterating relics of the past.

https://amanoempire.com/like-iron-lace/

404 (рекомендации местных жителей)

Old Havana

Ironwork in Cuban colonial architecture acquired a gradual

leading role resulting from the use of simple elements such as

door fittings, wrought iron door knockers and handles, wrought iron nails on doors and the addition of a novel, late 18th century device, the lamp bracket, which began to be used for street lighting. Pre-manufactured or ready-to-assemble products brought by way of companies based in Spain, England, the United States, France, Germany and Belgium coexisted with pieces forged in Cuban workshops.

The golden age and heyday of blacksmithing is evident in

19th-century architecture, which is classified as essentially

neoclassical. Wrought-iron railings, iron bars for balcony

structures and wrought iron gates on stairs were built in

Havana’s foundries under the influence of the use of ironwork

in architecture in such Spanish cities as Madrid, Seville and

Cadiz. This new trend brought a penchant for modernizing the appearance of historical buildings, but it did not come without criticism. The 20th-century scholar Francisco Prat Puig described the supporters of the trend as arrogant and irreverent for destroying or adulterating relics of the past.

https://amanoempire.com/like-iron-lace/